Zheng He, Pax Ming, and Southeast Asia’s First Colonial Age

How the Confucian tributary system sparked an early colonial enterprise in the 15th century.

One question that’s always bothered me, is why China didn’t become the dominant colonial power in Southeast Asia instead of the European powers that traveled halfway around the world. With its peripheral location to the great Southeast Asian archipelago, it had every reason to follow its growing diaspora with political and mercantile control. Were geography destiny, China should have been an expansive maritime power with all of the technological benefits that come with it. This post is about China’s one-time bid for hegemony in Southeast Asia and how history may have been very different if it had happened a century later or if the Europeans had arrived 50 years earlier.

In the past, I’ve written about how China provided much of the labor and a not insignificant part of the capital that made the European colonial project in Southeast Asia work. The migration of Chinese into Southeast Asia was a process that unfolded over centuries, driven by China’s substantial commercial interests in the trade that flowed from the region. That article looks at how the European imperial project in the region was based to a significant extent on the free flow of Chinese subjects beyond the reach of the imperial Chinese state. However, less than a century before the Europeans arrived, China engaged in its own imperial project in Southeast Asia as the Ming, at its height, sought to stretch its long arm across Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean.

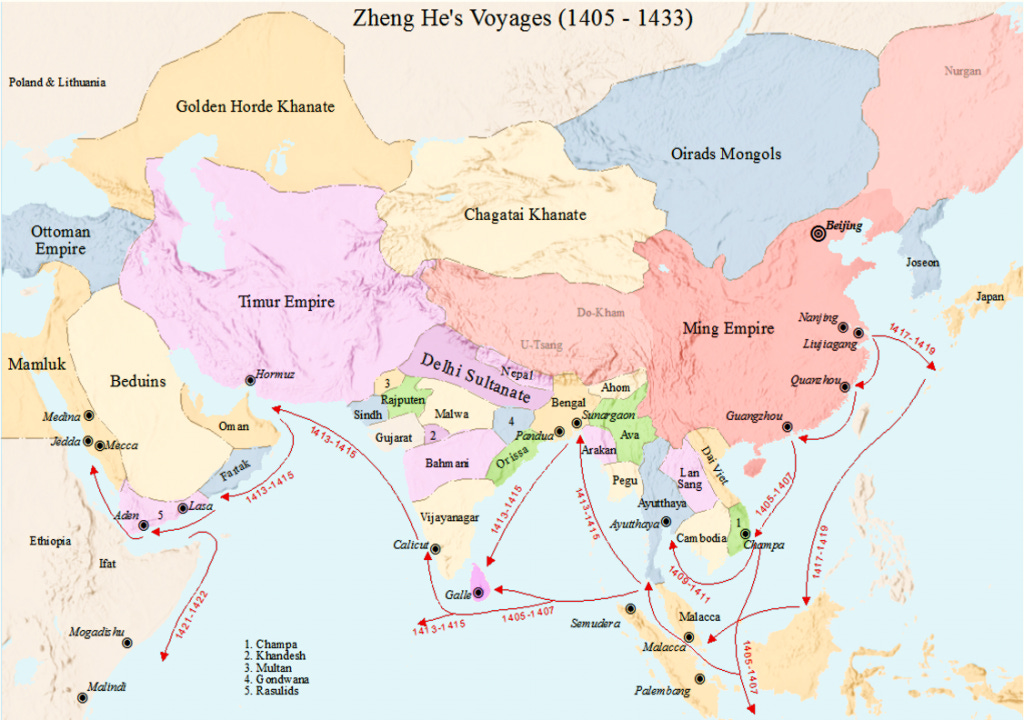

Most people familiar with the history of China and Southeast Asia know of Zheng He, the eunuch admiral of the Ming, who led the greatest armada the world had ever seen on seven journeys through Southeast Asia, reaching as far as the Middle East and the east coast of Africa. As the story goes, the legendary admiral led these expeditions throughout a remarkable 30-year career at the head of the Ming navy. Following his death, his fleet was dismantled on orders from the emperor, after which China never owned the seas again.

As with many historical narratives about China, the story of Zheng He is oversimplified. His voyages weren’t a unitary move to explore and create tribute relations with the southern ‘barbarians.’ Instead, they were part of an aggressive and integrated campaign to control the geopolitical landscape, foster state-monopolized trade, and extend imperial hegemony into regions it had never before ventured into.

A toehold in Southeast Asia

The Ming dynasty’s interest in Southeast Asia originated with the dynasty’s founding as early as the 1370s. The capital was located in Nanjing instead of Beijing or Xi’an, serving to orient the emerging state away from security concerns on the step and towards expansion into the more resource-rich areas of inland Southeast Asia. These efforts started as expeditions against the Tai polities that inhabited the mountainous region around Yunnan, as well as the reconquest of the Đại Việt and the Red River delta around modern Hanoi.

These southward commitments pulled the Ming gradually more into the region’s geopolitics, forcing diplomatic interactions and occasional military adventurism into the states of mainland Southeast Asia, including the Champa, Siam, and Burma, among many others. The mix of divide and conquer tactics, co-opting secondary powers, economic exploitation, and a Confucian ‘civilizing mission’ are eerily reminiscent of European powers’ approach toward colonialism in the coming centuries.

The preferred foreign policy tool for much of Chinese history is the tribute system, through which tributary states periodically sent emissaries to the Chinese court. The ritual component of the tributary relationship was intended to reinforce the Confucian geopolitical hierarchy. In practice, though, its main benefit for both parties amounted to state-monopolized trade. Here, the Ming’s imperial strategy differed dramatically from that of the mercantile empires of Europe. As it developed state-driven trade through its tributary relationships, it simultaneously sought to curtail private trade, going so far as to forbid its subjects from embarking on unofficial travel beyond its border. However, these prohibitions were of dubious effectiveness.

Zheng He and the expanding footprint of empire

Zheng He’s voyages are generally characterized as treasure fleets, used to extend the tributary relationship between China and the nations of Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. While they were built on a scale intended to produce awe, they’re usually described as being peaceful. However, it’s essential to understand these voyages as tools of Ming imperialism in the region. They were used to support an empire with active interests across Southeast Asia, which ultimately amounted to ‘gunboat diplomacy.’

The Ming treasure fleets were tools of legitimacy used to intimidate, display might, and collect treasure for the court from polities in the region as part of the tributary system. They also brought thousands of soldiers, including cavalry and artillery, making them effective instruments of force projection across the archipelago. The pattern of military interventions against recalcitrant leaders and in support of preferred factions in local civil conflicts show both a desire and the capability to mold the political situation across the region to support Ming objectives. These interventions include involvement in the Java civil war in 1407, anti-piracy operations in Sumatra that same year, regime change in Sri Lanka in 1411, and participation in a civil war on Sumatra in 1414 or 1415.1

As is the case today, supporting expansive naval operations far from home requires bases and military infrastructure in foreign lands to support long-range fleets. The Ming did this as well, supporting a friendly government in the state of Malacca, which was willing to allow it to establish a base in the Malacca Strait. Control of this vital waterway allowed dominance over one of the largest naval choke points in the world and has been the focal point for every power seeking to dominate shipping in Southeast Asia since.

In addition to the naval garrison at Malacca, they seized upon the presence of a large number of overseas Chinese living in Old Port near Palembang on the island of Sumatra to seize the city as a pacification superintendency in 1407. This designation gave it the same status as territories on the empire's periphery attained through conquest. By all accounts, The Ming had established an overseas colony populated with the empire’s subjects on the island of Sumatra. The use of the empire’s administrative designation for areas acquired through imperial expansion further supports the colonial nature of the enterprise.

These overseas bases would ultimately remain in the Ming's hands and support naval operations across the region for another 30 years until it gradually withdrew from naval engagement with the region in the 1430s, first prompted by emperor Xuan-Zong and accelerated by his predecessors. With the grounding of the treasure fleets and the reduced footprints in maritime Southeast Asia, the Ming was nevertheless still an active participant on its borders in mainland Southeast Asia, continuing to mount expeditions, demand tribute, and pick political favorites throughout the remainder of the century.

The legacy of Ming hegemony

The 40-50-year period of maritime engagement with the Southeast Asian archipelago isn’t long by the standards of empire. By contrast, the Dutch, who would arrive 200 years later, operated in the region directly and under the VOC corporation from 1602 until 1949, a stretch of nearly 350 years. Despite this short stretch, the Ming’s participation in the region reordered it significantly.

Commercial and cultural connections grew dramatically as the Chinese diaspora swelled in the region, forming many of the early Chinese communities that can now be found in the area. This connection would continue to boom. Essentially, the Ming expansion participated in and furthered the connection of global economic systems that began during this period. This process foreshadowed the European colonial age, which would begin to arrive in the region within 70 years of Zheng He's death.

Geopolitically, power dynamics between local states shifted as the Ming favored and intervened on one side or another. However, Ming favorites weren’t the only ones to get a leg up. The Đại Việt, who suffered under a 20-year occupation, emerged from the experience with a new command of gunpowder weaponry. The production and deployment of muskets and cannons allowed the Đại Việt to expand south, pushing back the Cham and eventually toppling them.

The Ming eventually withdrew from the region, retrenched itself at home, and focused on securing the northern border, from which its end would eventually arrive. The gap between the Ming withdrawal and the first European arrival was less than 100 years. It’s easy to imagine an alternative history where Europe and China met and competed for maritime and commercial dominance in the Indian Ocean instead of on the Chinese coast. And imagine they do. One of the reasons this chapter of history is both fascinating and important is that the prerogatives this most quintessential of Chinese dynasties enjoyed in Southeast Asia provide many of the justifications for how the CCP approaches the region, from its actions in the South China Sea to its flip-flopping approach to its diaspora. While it continues to insist that its intentions in the region are peaceful, it also remains nostalgic for a period when it was able to use coercion to reorder the region to its liking.

I found much of the historical detail for the events of this period in one article, “Engaging the South: Ming China and Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century,” which provides a far more detailed analysis of Ming engagement with the region than other sources I’ve found.

China was briefly a *maritime* player, but I’d dispute that they were ever (until very recently) more than a very localized naval power. By the time Zheng He was completing his voyages, European and Muslim powers in Northern Europe and the Mediterranean were engaging in regular, large naval battles that often involved rudimentary cannons.

While Zheng He’s ships were very big and expensive (far beyond a European equivalent at the time), I think it’s the consensus that they were technologically inferior to the emerging carrack designs for most purposes other than being a (very large) physical manifestation of China’s (very large) wealth.

Interesting and enlightening. You are right that history may be different if this happened a century later. First mover at a disadvantage here. Incidentally, I wrote about Melaka and briefly about Zheng He in my recent post: https://peckgee.substack.com/p/dimensions-of-diversity