Ho Chi Minh, A True Communist?

What Vietnam's messaging to the West tells us about the role of communism in national independence

I’ve been quiet on Substack over the last couple of months while I wrap up some larger research projects to close out the fall term. One of them focused on Vietnam’s communications with the West in the aftermath of WWII, which I thought would fit well here in a slightly abbreviated format as an in-depth look at a little-known part of modern history.

The years immediately following World War II were a period of immense structural tumult and intellectual ferment worldwide. World War II accelerated the collapse of the previously dominant European empires, denuding them of their colonial possessions in a global upheaval of independence movements that rendered them secondary players to a newly emerging pair of diametrically opposed superpowers. Within this global context, anti-colonial struggles around the world emerged as the front lines in the contest to reshape the global order. One of the conflicts that stand out for the scale of its human tragedy, as well as how unnecessary much of the conflict was, is Vietnam’s struggle for independence.

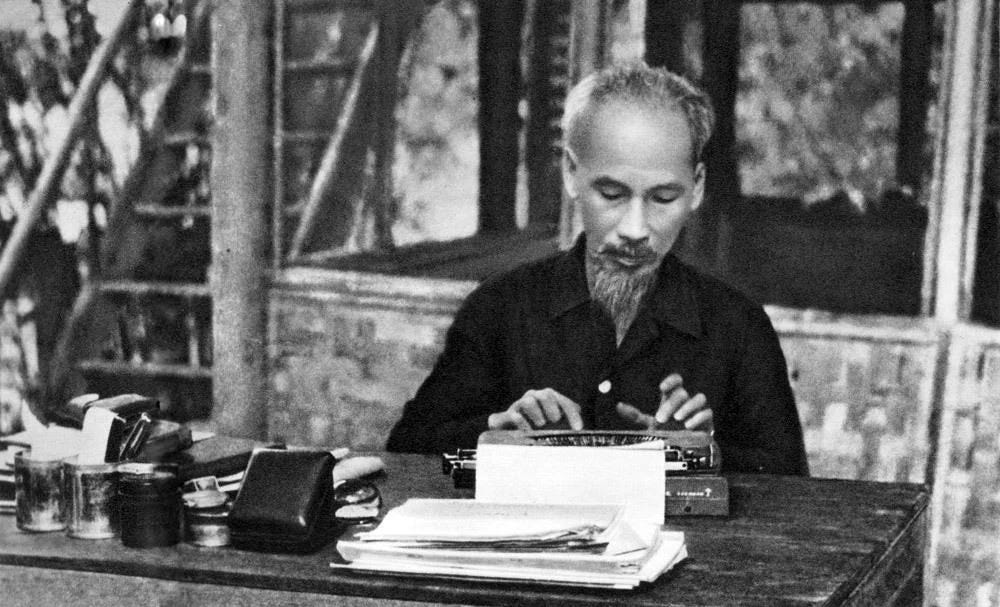

At the center of the early years of Vietnam’s quest for independence was Ho Chi Minh, one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the world’s 20th-century anti-colonial struggles. At various times over his life and the years since, Ho was branded a criminal, freedom fighter, national savior, republican, and communist. A lot of ink has been spilled since the conclusion of Vietnam’s wars for independence. But who was he, and to what extent was he genuinely motivated by communism as an ideology versus using it as a vehicle to mobilize a new nation to seek self-determination?

In the last couple of months, I’ve had the opportunity to explore this question through Vietnam’s communications with the West between 1945 and 1950. That five-year period is of particular curiosity because it was a transitional phase between World War II and the Cold War, as the Soviet Union and the United States transitioned from war-time allies to ideological and geopolitical rivals. This transitional phase offered independence leaders in European colonies around the world greater latitude to explore ideological and practical approaches to nation-building that cut across the Cold War’s demarcations between communism and capitalism.

Within this backdrop, Vietnam’s strategic communication with the West showed how the narratives of communism and nationalism evolved from the emergence of the Viet Minh at the head of an independent Vietnam in 1945 to their eventual recognition by the Soviet Union in 1950. From these sources, Ho Chi Minh emerged as a nationalist first who sought to cultivate a constructive relationship with the US and an ally of international communism only out of necessity when the former option failed.

A Request for Help

On February 28, 1946, with the United States, the dominant power in the Pacific, and the Soviet Union consumed with rebuilding following the war, the little-known leader of the Viet Minh, Ho Chi Minh, reached out to President Truman by telegram. In this telegram, Ho accuses the French of attempting to overthrow the newly formed republic and appeals for US support, citing the US’s support for the principle of national self-determination. Ho’s appeal to aid shows that the ideological battle lines of the Cold War had not yet solidified.

While a communist with a long record of writings on the role of socialism in the anti-colonial struggle, Ho also drew heavily from America’s own anti-colonial struggle and aversion to the European colonialism of the 19th and 20th centuries.1 This is reflected not only in the language of the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence but in Ho’s telegram to Truman, in which he invokes the Atlantic and San Francisco Charters, in which the Allies laid out the basis for the right to self-determination by nations following the war.

In a democracy, the press is crucial in shaping public understanding and opinion on foreign policy matters. Because of the role of media in forming public opinion, it is telling that Ho’s telegram was classified by the US government, making it not a part of the broader public discourse about the emerging conflict. Because of this, there is little indication of an informed debate within the media regarding the cause of independence in Vietnam or the wisdom of America backing French attempts to regain control of their colony. Despite this gap in the public discourse surrounding America’s Indochina policy at the time, sources within the government were making these arguments.

Col. Archimedes Patti was an intelligence officer in the OSS who was active in Indochina in the last year of World War II and maintained direct contact with Ho Chi Minh. His presence and analysis provide a valuable perspective on Vietnam’s early struggle for independence.

Thanks to his intelligence briefs and oral interview, we have a detailed understanding of Pattie’s analysis from the period and his reflections on the experience from 26 years later. In Patti’s words:

It was, it was a terrible situation. No, it need not have happened. It happened. But, we had every reason to not let it happen. Ho Chi Minh was on a silver platter in 1945. We had him. He was willing to, to be a democratic republic, if nothing else. Socialist yes, but a democratic republican. He was leaning not towards the Soviet Union, which at the time he told me that USSR could not assist him, could not help him because they just los—won a war only by dint of real heroism. And they were in no position to help anyone. So really, we had Ho Chi Minh, we had the Viet Minh, we had the Indochina question in our hand, but for reasons which defy good logic we find today that we supported the French for a war which they themselves dubbed “la sale guerre,” the dirty war, and we paid to the tune of 80 percent of the cost of that French war and then we picked up 100 percent of the American-Vietnam War. That is about it in a nutshell.

The failures that Patti alleges could be summarized as a policy of willful ignorance and obfuscation by the Truman administration. Ho Chi Minh’s telegraph to Truman was not only ignored but also classified, limiting discussion of the political options available to the US in Indochina.

In his interview, Patti recalls his discovery that his intelligence briefs had never been removed from their original wrapping. They had never been read. Furthermore, despite occupying high-level foreign policy positions and being one of the few people with on-the-ground experience in Indochina, Patti claims he was never once consulted by the administration regarding Ho Chi Minh. While arguments are often made that US support for the French revolved around their need to secure France as an anti-communist partner in Europe, the lack of any engagement with the intelligence assessments coming from Indochina suggests that this policy was less a strategic calculation than a policy default by a US ill-equipped for the choices posed by its emerging hegemony.

Media coverage of the French reoccupation

Public pressure can often constrain the policy choices of politicians, even in cases of international relations. Because of this dynamic, it is important to ask if the Truman administration was under public pressure to pursue a hardline policy in Indochina. This is plausible since the period between 1945 and 1950 saw a transition in the public perception of the Soviet Union from wartime ally to geopolitical and ideological rival. If this pressure existed, the discussion of supporting the French as an anti-communist bulwark and Viet Minh’s communist affiliation would likely be represented in media coverage as a critical conduit for shaping the narrative and public understanding of those events. However, a survey of articles from 1946 covering the escalating situation in Indochina not only does not indicate public pressure but also draws no direct connection between the Viet Minh and communism.

In December 1946, the Washington Post ran an article on talks between Ho Chi Minh and the French seeking a cease-fire. The article focuses on French maneuvers in the region and on the attempts to find a resolution. It details the Vietnamese goals in the ceasefire talks, which focus on incorporating Cochin China (a region of French Indochina) into the new republic. The French perspective on the Viet Minh, according to the article, is that they are outlaws, although unlikely to be removed from the political picture. Indeed, the only reference to socialism is regarding Louis Caput, an observer from the French Socialist Party who favored a compromise. The involvement of the French Socialist Party, however tenuous, could indicate that the concern over the spread of communism animating American foreign policy in the region was concern over French Communism, not Vietnamese.

In other papers from the time, the lack of any reference to communism in Indochina is notable. In the Hindustan Times, a newspaper in British India with nationalist leanings, an article from five days earlier highlights the movement of French forces into the region. It showcases Ho’s accusation that it is the French provoking conflict. On a paper filled with articles focused on liberation movements in European colonies, this article also makes no mention of Vietnam’s communist affiliations. Instead, it focuses on Ho Chi Minh’s role as a nationalist independence leader and an anti-colonialist.

A similar story is told in an article from nine months earlier in the March 5th edition of Daily Worker, a communist-leaning newspaper in the US. Like the Hindustan Times, on a page filled with articles about independence and anti-colonial struggles around the world, the Daily Worker was happy to showcase it as an example of injustice in the Western colonial order. However, it makes no reference to any communist affiliation. It seems unlikely that a newspaper deeply aligned with the cause of international communism and clearly focused on the progress of the liberation movement would miss a chance to showcase the presence of communism as a pivotal factor in driving a revolution forward.

The absence of any explicit linkage between the fledgling Vietnamese republic and the international communism made within these articles casts doubt on its existence. Coupled with Pattie’s observations from the year before and Ho’s telegram that February, it is likely that Ho had found communism useful as a means of mobilizing a peasantry against the colonial apparatus of the French and Japanese but found limited ideological influence beyond that and further sought to prevent communism from writing Vietnam’s geopolitical destiny beyond its borders.

Rejection and a pivot toward the Soviet camp

Despite the conciliatory approach toward the West in 1946, things had changed by 1949, indicating that Vietnam now sought inclusion in the communist camp. This is demonstrated by a shift in Vietnam’s messaging to the world, indicating a desire to remove any ambiguity about their allegiances. By August 1949, the state-run Viet Nam News Agency was working to solidify Ho Chi Minh’s communist bona fides. In one dispatch, “Ho Chi Minh Prove A ‘True Communist,’” they explicitly link Ho to communism while acknowledging that the Soviet Union had not come to the defense of Vietnam.

The dramatic shift in tone between this proclamation and the language used by Ho and others to describe the Vietnamese cause obscure what was likely a more gradual transition over the intervening years leading to the recognition of the Democratic Republic of Given the shift in rhetoric from an official Vietnamese channel, coupled with the proximate recognition by the communist bloc, statements such as this should be understood to represent a strategic shift in Vietnam’s messaging caused by a recognition of its failure to engage US support and the need to retain an alternative source of support and legitimacy. Given their muted embrace of communism through the rest of the decade, they now sought to incontrovertibly link themselves with the communist bloc to legitimize their fight in the communist world that was, by this point, in far more explicit contention with the West.

A flexible origin story

International messaging tends to be a calculated and highly strategic affair where authenticity is often distorted or rewritten to serve the political objectives of the moment. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, emerging nationalist leaders like Ho navigated a dynamic ideological and geopolitical environment to mobilize national support while appealing to Western ideals of self-determination.

However, by 1949, the moment of opportunity created by the transition from World War II to the Cold War was ending. Despite the Vietnamese's reduced space for diplomatic maneuvers, some latitude remained. Even as Ho’s ties to the communist bloc deepened, his presence at Bandung five years later and his rhetoric while there indicated a consistent desire to see Vietnam chart its own path internationally. Despite this ideological alignment with the other members of the conference, the North Vietnam delegation was largely sidelined at the conference due to their entanglement with the Soviet Union. Ho’s participation in and ideological alignment with the other nationalist anti-colonial movements show that despite deepening ties with the Communist bloc, he still sought to define Vietnam’s struggle for independence in national terms and chart a course for the country unrestricted by the Cold War's geopolitical realities.

The description of Ho Chi Minh as a “True Communist” in 1949, given his messaging in previous years, could be driven by a natural evolution in Ho’s politics, demonstrating a conclusion that communism offered the most effective path to the political mobilization of the nation in its fight for independence. Alternatively, it might represent a pragmatic shift based on a calculation that Vietnam would need external aid in its fight for independence and that he was mostly likely to find that aid in the communist bloc. Vietnam’s messaging on this issue leaves this question open as a matter of conjecture. However, what’s known about Ho’s participation in Bandung five years later illustrates Ho as an enduring nationalist leader who had only reluctantly turned to the communist world for support when his efforts elsewhere had failed.

The complexity of Ho Chi Minh’s political thinking and the vision he sought for his country became victims of the Cold War. Combined, these documents illustrate a nuanced set of goals framed in a sophisticated understanding of geopolitics, which had to compete aggressively on the world stage in order to attract support for the movement. In February 1946, Ho sent a telegram to President Truman asking for support in Vietnam’s negotiation with the French for independence. In his telegram, he cites “the principles of the Atlantic and San Francisco carters” and does not refer to communism. While the telegram is a request for help and not intended as a political treatise, it suggests a pragmatic willingness to seek partners outside communist circles. This willingness is corroborated by Col. Patti’s intelligence assessments from Vietnam in 1945. Furthermore, his reflections on that time 26 years later show Ho as more focused on national liberation than communist ideology and a willing partner to the US. Similarly, in the press from the time, Ho is portrayed as a nationalist instead of a communist, even in publications that would have been sympathetic to his communist ties.

The evolution of Vietnamese strategic messaging to the West shows an independence movement that was willing to use the tools socialism provided to mobilize an emerging nation but did not seek to be internationally defined by that affiliation. This nuance was lost on US policymakers in the hostile and ideologically charged environment of the early Cold War. As Patti observed, the unwillingness of the US foreign policy establishment to engage with multiple streams of information coming from the region in the aftermath of World War II squandered an opportunity to build a partnership with Ho and instead put the region on a trajectory for tragedy that ultimately would see Vietnam become a durable member of the communist bloc and which ought to serve as an enduring warning to the consequences of ideological myopia for contemporary policymakers.

Hồ, Chí Minh. Selected Works of Hồ Chí Minh. Works of Maoism, #13. Paris: Foreign languages press, 2021.