The Southeast Asian Scam Epidemic

How politically contested spaces are empowering organized crime

This post originally started as one about the gambling sector in Southeast Asia, which is an interesting topic in its own right and one that I may return to in the future. However, to understand the costs of the gambling industry in Southeast Asia, one must understand the landscape of organized crime and how it touches so many other aspects of regional economies. A while back, I remember a conversation with my language teacher about how out-of-control scammers have become in Vietnam. This made sense. After all, the number of scammers and robocallers in the US also seems fairly out of control. At the time, I didn’t realize the full extent of the issue in Vietnam or that it was not specifically a Vietnamese issue but one affecting all of Southeast Asia. The problem has reached such epidemic proportions that it is attracting the attention of the UN as well as US and Chinese law enforcement.

To refer to these operations as industrial-scale criminality almost understates their reach and power. Though not on the scale of the drug cartels active in the Americas, who collectively make hundreds of billions of dollars, the scam operations in Southeast Asia nevertheless rake in billions of dollars annually using operations that involve hundreds of thousands of people spread over numerous countries. To put it in perspective, an article from the Diplomat detailing the UN’s report cites organized crime as making up nearly half of one unnamed country’s GDP, with their estimate landing between $7.5-12.5 billion annually.

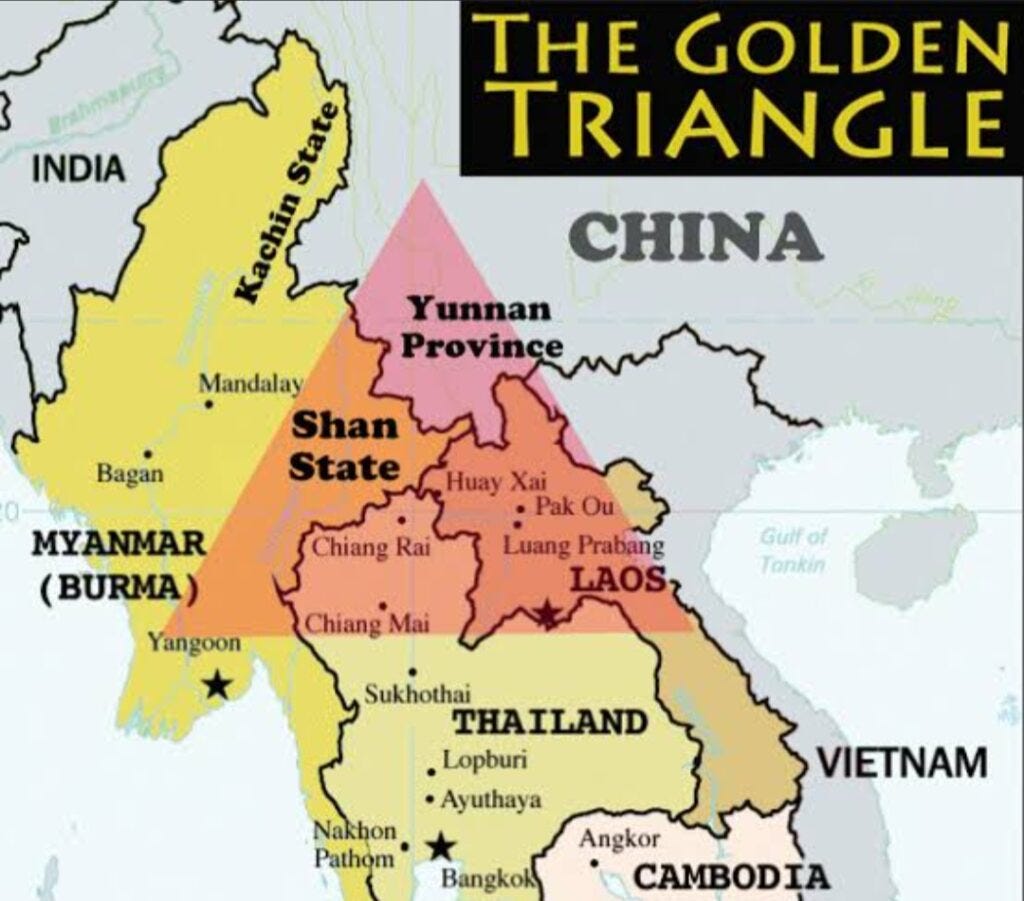

The Golden Triangle

Organized crime in Southeast Asia has historically concentrated in a few port cities and, especially, within a region known as the Golden Triangle. So named for the wealth the region produces from drug production and other criminal enterprises, the Golden Triangle is a region straddling the Mekong, which covers parts of northern Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, and China’s Yunnan province. Organized crime is able to take advantage of the low state capacity and porous borders within the region to engage in criminal enterprise and even carve out a level of autonomy where they’re relatively free from state interference.

Within the Golden Triangle, two areas in particular stand out as epicenters of criminal activity. Myanmar, with its decades-long civil wars and the recent near collapse of the central state altogether, has long played host to many seedy industries. In the current conflict, the demand for weapons produces a steady need for new revenue streams, and the presence of vulnerable displaced populations creates a workforce that can easily be exploited. The playbook appears somewhat similar on the other side of the Mekong in Lao’s special economic zone, which is also a hotbed for criminality under the operation of Zhao Wei, a gangster and business tycoon of Chinese origin who crosses legitimate and illegal operations within his enterprises.

Drugs have been a long-running problem originating from this region, and account for the draconian drug laws countries in Southeast Asia are known for. With drugs come an assortment of other crimes, from violence and money laundering to human and wildlife trafficking. In recent years, this infrastructure has been turned to fuel the boom in online scamming that is taking the region by storm. Many of these criminal enterprises also have roots in the burgeoning gambling industry that has exploded across the region as the newly wealthy in Southeast Asia and China look for ways to enjoy their money.

Online scamming has exploded in popularity among gangs because it is low overhead and low risk relative to drug smuggling. Vulnerable people who are looking for work and often lack papers get conned into fake jobs by human traffickers. These people, many of whom are educated and computer-literate victims of the conflict in Myanmar, find themselves imprisoned in fortified “scam compounds” where they serve as forced labor in what is essentially a criminal call center.

International Enforcement Efforts

Thus far, the region and the world have struggled to effectively police crime in the region, including the often difficult-to-trace and highly mobile world of online scamming, even as it grows in scale to threaten stability in the region. ASEAN released a plan of action for combating transnational crime in 2017, intended to address this issue among other issues related to transnational crime. The UN has also played a pivotal role in bringing awareness to the scale of the issue following a report in 2023. Both Chinese and US law enforcement agencies also actively engage with countries in the region to address organized crime.

For its part, ASEAN’s plan of action promises cooperation between actors and lays out a general framework but stops short of substantive declarations. Meanwhile, other documents on Combating Transnational Crime in ASEAN and Managing Transnational Crime in ASEAN date back to 1999. As is always the case with ASEAN, it functions as more of a coordinating body, stopping short of binding commitments or direct action.

The US, which can also be a target of these scam operations, has a lot to offer the region in helping to curb organized crime as it seeks to deepen ties with it. It can build on existing security partnerships to include things like joint coast guard patrols to deter smuggling and piracy, assist in training law enforcement, or coordinate international efforts to roll up crime rings. Furthermore, the US’s continuing hold over the global financial sector through institutions such as SWIFT provides some of the most effective tools to curb transnational crime.

China, which shares a long border with ASEAN, including the Golden Triangle, and with a significant human connection to both organized crime in the region and the industries that fuel it, has deep and complex interests in mitigating regional crime as a threat. Accordingly, China has pursed controversial plans to deepen law enforcement cooperation between states in the Golden Triangle, pushing for the active participation of Chinese police in Thailand and Laos. These initiatives, at times, have come with pushback from local politicians, as they did recently in Thailand. However, at other times, Chinese law enforcement has been instrumental in rolling up criminal operations, as was the case with their anti-piracy patrols following the 2011 massacre of 13 Chinese nationals on the upper Mekong, as well as cooperating with militias in raids on illegal scamming operations in Northern Myanmar in 2023.

While some states in Southeast Asia, such as Thailand, likely have the capacity to manage enforcement effectively within their borders, others, like Laos and Myanmar, do not. This makes international efforts to root out criminal networks essential. Nevertheless, without addressing the root causes, allowing these networks to operate with relative impunity across the Golden Triangle makes enforcement more of a bandaid than a lasting solution. Despite this, enforcement will likely remain the only realistic way of addressing the issue in the coming years. This will in turn continue to fuel engagement between the region and outside powers to curtail common threats. It remains to be seen if these efforts will in turn begin to play into the broader logic of geopolitical influence and competition playing out between the US and China, as both sides seek to deepen their involvement in Southeast Asia.

The scale of these operations is simply astonishing. I live in Vietnam and while it's a strong enough state to not have the 'scam compounds' present in Cambodia and Laos, digital scams are still rampant and take on truly incredible forms.

Glad you are spotlighting this highly concerning situation in SEA. It has trapped young people from Malaysia, Singapore in the name of jobs and even love as well!