Probably nowhere else is the full scope of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) more on display than in China’s attempt to connect Singapore by rail directly to China. First proposed in 1995, it’s a project of both economic and symbolic significance, which plainly shows the reach of modern China and brings Southeast Asia much closer. The Strait of Malacca, on which Singapore is located, is the busiest maritime chokepoint in the world, through which 25% of world trade runs. When complete, the project will open up vast stretches of inland Southeast Asia and Southern China to trade flowing overland from the Indian Ocean. It’s a project that will shape the economic development of the entire region and comes with many geopolitical implications.

The Singapore-Kunming Rail Link could be better described as a regional network connecting several intermediate points across all mainland Southeast Asian countries. Many parts of Southeast Asia have long been under-served by modern infrastructure, instead relying on rotting colonial roads and railways established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As the region develops, this is gradually changing, with new highways and rail lines being built to connect the region's economic hubs, but take an exit off of those shiny new highways, and one can quickly find oneself in a different era of infrastructure. Many countries eagerly seek China’s investment in these projects. However, its leadership in the region’s infrastructure plans leads to unease in some corners.

Scope of the project

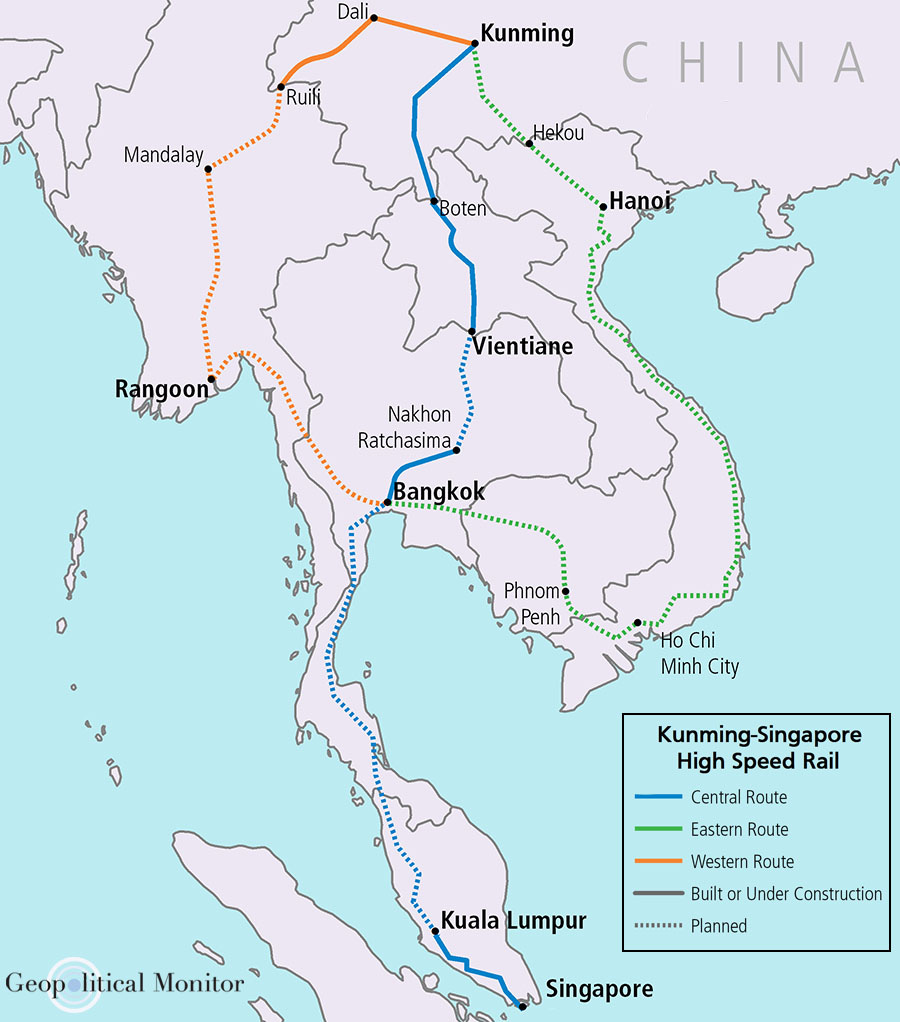

The project is more of an umbrella initiative providing a guiding vision for several smaller rail projects connecting different Southeast Asian cities. The Singapore-Kunming rail link includes tracks being laid or planned in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, and even war-torn Myanmar, creating a network stretching across the entire region. Many of these rail lines connecting metropolitan hubs make economic sense in their own right, and the hope with the project is that these links would provide sufficient revenue to subsidize the less cost-effective links.

Troublingly, many of these less economically viable pieces of the network fall in the poorest countries in the region, notably Laos, creating concerns over the creation of debt traps and who would be responsible for them. It is worth noting that concerns over the debt and financial viability of projects frequently follow BRI projects. The most infamous example is probably the challenges Sri Lanka has had with its deepwater port, which was funded and built by China. While debt traps and investments with strings attached are always a concern for developing countries, it’s difficult to frame BRI projects as inherently predatory. As Sri Lanka’s success in renegotiating its infrastructure debt shows, small countries still have agency in their foreign partnerships and are capable of navigating the treacherous world of foreign aid to successfully meet their goals.

The project itself has been coming for a long time. It was first proposed in 1995 at the fifth summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), long before the Belt and Road Initiative existed. The first link in the network, connecting Phnom Penh to Bangkok, started in 2007. The larger project linking the two terminus points is expected to be completed in 2027. While many of the most important lines in the network are moving forward more or less as planned, it remains to be seen if the entire network that’s been envisioned will be completed or if some of its less viable lines will be pared from the final network.

Hurdles and Risks

While reception to the project has been broadly positive, and thus far, many of the linkages have made progress, the overarching project isn’t without its challenges. The project involves coordinating the interests of seven countries over a twenty-year time horizon, which is a fairly remarkable feat of international collaboration.

One of the challenges is that while this may be China’s brainchild, they are not the only provider in the region competing for infrastructure contracts. The Japanese, in particular, have been highly competitive in pursuing infrastructural development projects across the region. The Chinese have a specific approach to development, which emphasizes the use of Chinese technology, companies, and labor to get the job done. This is contrasted against most other countries, which will generally seek a more collaborative approach to projects utilizing domestic labor in the project country. The result for China is an emphasis on exporting its overcapacity in the Chinese construction sector while maintaining control over the technologies used. If extra partners become involved in building different lines of track, China will likely have to be open to sharing technologies with those partners to ensure the system’s interoperability.

Speaking of interoperability, there is no more fundamental aspect to railroad connection than the gauge of the track used. Internationally, there is no real standard for track gauge, so connecting different countries can be a challenge. As you’ll see in the map below, the rail standards used across Southeast Asia are smaller than those typically used by China, dating back to the colonial era, and less capable of handling high-speed rail. ASEAN countries are coming down on different sides of this decision, with the Laos portion moving forward on Chinese standards while Vietnam is reluctant to move off its national standard for the project. Reluctance to let China set rail standards internationally is both a political issue and one of cost in updating the remainder of their domestic network. However, regardless of who’s standard gets adopted for this line, there’s still an interoperability issue requiring transfer between trains for transitions between local legaacy lines and international links.

Another area of concern in the project that is often dismissed but shouldn’t be is the input from local communities disrupted by the projects. BRI projects have a less-than-stellar record of considering community and environmental concerns. The Singapore-Kunming rail link is no exception. For any society, there’s a delicate trade-off between taking care of local communities and stewarding natural resources versus accomplishing large-scale, high-impact projects that will help the country as a whole develop. I won’t pretend to have a satisfactory answer to how to balance these needs. Nevertheless, it's worth noting that when these projects demolish communities, they’re frequently the most vulnerable groups being ousted, and their limited ability to recover from the loss of property and community can be devastating.

What does this project mean for China and Southeast Asia?

When thinking about the implications of BRI, it’s easy to jump right into the geopolitical impacts of projects. To be sure, there are considerations for regional power and security. BRI is, in part, a soft-power campaign by China to develop influence in the developing world relative to other world powers. Rail connections to the Malacca Straight and the Bay of Bengal also allow Chinese supply chains to bypass critical maritime choke points in the event of conflict in the West Pacific. These are worth considering and could be a whole article on their own.

Southeast Asian countries aren’t blind to the geopolitical implications of BRI projects. Vietnam’s reticence to adopt Chinese rail standards seems to highlight their awareness of the issues of sovereignty and autonomy that are in play. However, these concerns can miss the point for many ASEAN leaders. They need development to support rapidly growing economies, and the BRI is a willing partner who can deliver.

Last week, I alluded to regional networks involved in manufacturing electric vehicles in Southeast Asia. Intra-regional transportation infrastructure like the Singapore-Kunming rail link is precisely the kind of project the region needs to support that sort of networked economic growth. While the Chinese are undoubtedly thinking of their ability to import and export from the Indian Ocean, Southeast Asian factories will also be able to ship to the Chinese market with greater ease and import precursors to power that manufacturing. Lastly, overland networks connect more regions in inland Southeast Asia to the global market, meaning development no longer needs to occur primarily along the coastline, as has mainly been the case.

Countries are often keen to talk about their plans for mega projects, but many of them never see the light of day. Credit where it’s due; the Singapore-Kunming rail link has wheels and rails to run on. In a rapidly changing region, this project will move the region forward and hopefully pull it closer together.